Key Findings

- Businesses invest now to earn future returns. For an investment to be worthwhile, it must at least “break even,” providing a risk-free return that covers the cost of capital, time, and inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers fewer goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power.—known as the “normal” return to investment.

- Businesses can also earn supernormal returns, which exceed the normal return, often due to unique advantages like market power, rent-seeking, investment risk, or temporary pricing power due to innovation.

- The impact of taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. policy on investment decisions depends on the type of return the investment generates. Normal returns are the most affected by taxes, supernormal returns from risk and innovation are still responsive, and supernormal returns from market power are the least responsive.

- To encourage investment, the tax system should exempt normal returns, as they directly impact new investments at the margin, or the breakeven point for businesses.

- Taxing supernormal returns can still be economically counterproductive, as these returns often come from risky or entrepreneurial activity.

- Accordingly, arguments that the corporate tax can be raised with few economic trade-offs because supernormal returns constitute a substantial share of corporate profits should be viewed with skepticism.

- As Congress prepares to debate the upcoming expirations of the 2017 tax law, two policies under consideration would help exempt the normal return to capital: returning to expensing for research and development (R&D) costs and reinstating 100 percent bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs..

- Raising the corporate tax rate and other taxes on business investment would negatively impact innovation, entrepreneurship, and economic dynamism in the US, discouraging these productive activities.

Introduction to Supernormal Return on Investment

The future of the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. is a prominent issue in the presidential campaigns and debates over the expiring provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Major parts of the conversation include the headline tax rate, the deductibility of research and development (R&D) costs, equipment investment, the new corporate alternative minimum tax, and the international reforms (GILTI, FDII, and BEAT).

Disagreement among policymakers and analysts about the economic impact of the corporate income tax clouds the debate. The disagreement often stems from different understandings of how the economy works, including who really pays the corporate income tax and how the corporate income tax affects behavior.

One source of disagreement is the type of returns to investment in the US economy. Advocates of levying higher taxes on corporations argue that an increasing share of the corporate tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. contains a certain type of profit—supernormal returns—that may be taxed without much concern about economic impact.

In this paper, we critically examine the contention over the taxation of supernormal returns, reviewing what we know about supernormal returns, surveying the literature on whether the US economy has seen an uptick in these returns, and discussing the implications for tax policy.

There are a few main points to consider. One, slight methodological differences lead to drastically different estimates of the supernormal share of the return to capital. Two, not all sources of supernormal returns are pure rents: some, like temporary returns to innovation, are still responsive to taxation. Accordingly, the view that corporate income tax mostly falls on supernormal returns and therefore can be raised without significant economic harm should be viewed with considerable skepticism. In the context of the upcoming tax debate, the corporate income tax matters greatly.

What Is a Supernormal ReturnSupernormal returns are payoffs to investment greater than the typical market rate of return. They are often approximated as company profits that exceed 10 percent. This additional return on capital or labor is above breaking even on an investment relative to the amount of risk and time that investment required.?

To understand what a supernormal return is, one must first understand what a normal return is.

People value a dollar today more than a dollar a year from now. The future is uncertain, so you might want to spend that dollar today or have it with you in case of an emergency. Accordingly, people charge interest. For instance, if I want to borrow a dollar from you today, I might have to pay you back, say, a dollar and three cents a year from now, which equals a 3 percent interest rate.

By receiving interest, you are compensated for delaying your own consumption. The modern economy works according to this premise. Savers postpone their consumption to fund investments on the expectation that they will receive more than their dollar back in the future. Savers might fund investments through credit markets, lending money to businesses and institutions by buying bonds and receiving compensation in the form of interest payments. They might also fund investments through equity markets, by purchasing stock and receiving compensation through future dividend payments.[1] The compensation they receive is their return.

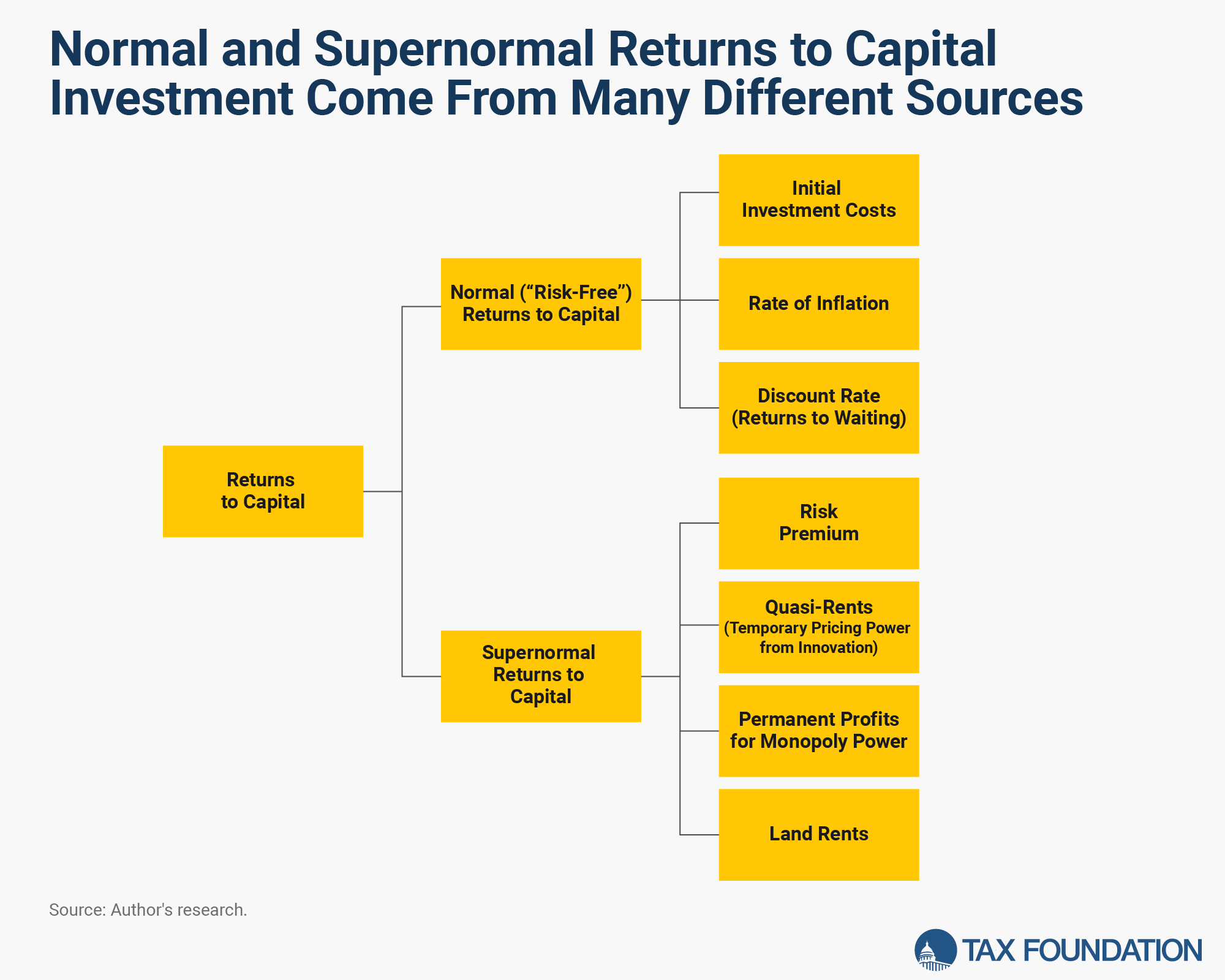

Normal and excess (or supernormal) returns are two basic types of returns.[2] The normal rate of return is simply the required payoff for delaying consumption. The normal rate of return is also often called the risk-free rate. Established and safe borrowers can borrow at the risk-free rate: they would like to make some form of investment or purchase today, and they will certainly (or with near certainty) be able to pay you back in a year, so you the saver only need compensation for delaying your consumption by a year. The supernormal return is anything earned on top of that normal return.

Under a perfect competition model, businesses earn a normal rate of return on investment: many firms sell non-differentiated products in the market, with prices driven down so profit margins are only wide enough to compensate investors for their delayed consumption. Under this model, therefore, any returns more than the normal rate of return must be a result of some violation of perfect competition. A firm may have market pricing power or even full monopoly power. It could also mean they benefit from pure economic rent, such as the appreciation of unimproved land. But not all violations of the perfect competition scenario or accruals of supernormal returns should be causes of concern.

One of the most common and important violations of perfect competition is risk. Investors are risk averse, as they do not have perfect information. Accordingly, to make a risky investment, the expected value of the return to a risky investment must be higher than the expected value of the return to a risk-free investment. The difference between the two is known as the risk premium. Some measures of normal returns include the risk premium to reflect a risk-adjusted normal return.[3]

Highly volatile commodities provide a good example of the returns to risk. In recent decades, the energy sector has been the most volatile of the stock market, as energy producers are both exposed to market risk (as demand for fossil fuels fluctuates with overall macroeconomic conditions) and geopolitical risk (as oil prices are heavily affected by certain international actors like OPEC).[4] In a year when oil prices unexpectedly boom, oil and gas producers may appear to earn supernormal profits, but the fat years of high profits are necessary to offset the heavy losses when oil prices collapse.[5]

R&D-intensive industries like biotechnology are also illustrative. Looking at the returns of major biotech companies in an individual year might lead one to conclude their high returns are the result of rents. But looking at successful biotech firms alone ignores the many biotech firms that fail—and the very real chance of failure necessitates a high return in the event of success. Companies need a very high potential return to risk investing billions in R&D that may not even yield a commercially viable product.

Fundamentally, companies need to deliver innovation to differentiate themselves. If a startup founder entered a pitch meeting with a venture capital firm and promised to deliver investors the returns of a Treasury bond or even the expected returns of the S&P 500 index, they would be laughed out of the room. Companies must offer the potential of greater returns to attract investment, usually in the form of some technological or process innovation that will grant at least temporary economic profit (i.e., supernormal returns) before the returns return to normal from competition.[6]

When looking only at the returns of profitable companies in an individual year, the profits of risk-takers and innovators may look indistinguishable from rents earned by market power. And at some level, they may be rents, at least temporarily. If an entrepreneur develops a new kind of product, they effectively have a monopoly on that product until competitors enter the market. In a pharmaceutical firm’s case, it may be a patent monopoly established legally through intellectual property law. New processes or technology can also take several years for other firms to integrate into their products or production.[7]

Once you subtract the risk premium and temporary rents (which are the same as returns to innovation), you are left with a remainder that more closely resembles true rents. Unimproved land is the classic example of economic rent: land appreciating without the owner making any investment or improvement. There also may be natural monopoly rents, when a company does hold a true monopoly on a good or service.

Supernormal Returns in the US Economy

Going beyond economic theory, what does the data say about supernormal returns in the US today? What share of the return to capital is supernormal, and of that share, which driving factors are most responsible?

These are difficult questions. William Gentry and Glenn Hubbard used 1980s stock market data to estimate that roughly 40 percent of corporate returns are normal returns.[8] Research using tax data from 1995 to 2001 showed normal returns constituted 32 percent of all corporate returns.[9] A 2012 Treasury Department update using tax data from 1999, 2000, 2001, 2004, and 2007 found 36 percent of the return to capital was from normal returns.[10] A 2016 Treasury Department update considering IRS data from 1992 to 2013 estimated the share of the normal returns had declined from 40 percent between 1992-2002 to 25 percent from 2003-2013.[11]

However, the existing literature has at least three methodological challenges. First, the studies rely largely on corporate sector data, ignoring the non-corporate business sector of the economy. Second, the Treasury’s methodology omits firms that are earning losses. And third, when looking at returns to capital, we should consider net rather than gross returns, which involves subtracting state and local taxes paid as well as interest paid. Changes to gross returns from factors not involving returns to capital should be excluded if we want to know how market returns have changed over time. When including the noncorporate sector, loss firms, and net returns, the estimated share of normal returns to capital is substantially higher, averaging 74 percent between 1968 and 2007.[12]

Setting these methodological debates aside, arguing about supernormal returns rising across the economy raises the question of what kind of supernormal returns are rising, and if that trend is necessarily harmful or necessitates a change in policy outlook. Factors other than monopoly power may explain the change.

The clearest missing piece of the analysis is changes in the risk premium. A rising share of supernormal returns might simply reflect the risk premium rising over time. Plenty of evidence points to a rising risk premium over the same period supernormal returns supposedly grew. In the years following the Great RecessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years., demand for risk-free assets grew and the risk-free rate of return fell dramatically, but the expected return on equities remained steady. Accordingly, the spread between the two (a solid benchmark for risk premium) grew.[13]

The 2016 Treasury Department study hypothesized the decline in the share of normal returns may have been due to the increasing importance of intangible investment.[14] In recent years, the composition of nonresidential business investment has shifted toward intellectual property, particularly research, development, and software. From 2007 to 2023, real business investment in intellectual property grew 153 percent, while real GDP grew 33 percent. R&D investment, a key subcomponent of intellectual property investment, grew 90 percent. Furthermore, intellectual property’s share of nonresidential fixed investment grew from 27 percent to 42 percent over the same window.[15]

We would reasonably expect a more R&D-intensive economy to produce more temporary quasi-rents. And industry-level analysis favors that hypothesis, as illustrated by an examination of the share of normal returns by industry in the 2016 Treasury Department study. It found normal returns were responsible for a large share of overall returns in utilities, construction, and mining; an average share of overall returns in wholesale and retail trade, transportation, and some forms of manufacturing; and a low share of overall returns in industries such as information, technology, and other forms of manufacturing, particularly chemical manufacturing.[16]

Not coincidentally, the share of normal returns appears to be negatively correlated with R&D intensity. Industries with high shares of normal returns (utilities, construction, and mining) all perform insignificant amounts of R&D, particularly relative to their sales. Industries like wholesale and retail trade with middling shares of normal returns are also middle-of-the-pack when it comes to R&D intensity. Meanwhile, information technology and chemical manufacturing are among the most R&D-intensive industries in the United States and have some of the smallest shares of normal returns.[17]

Three points are worth exploring further. First, returns to R&D investment, particularly in digital technology or services, may be higher than returns to physical capital. R&D investment could also involve taking more risk on average than physical capital, driving up required returns.

A second possible driver of an increase in supernormal returns is an increase in market concentration by larger firms, reducing competition and raising returns to capital investment. Proponents argue that concentration explains why investment has fallen despite rising returns